[et_pb_section admin_label=”section”]

[et_pb_row admin_label=”row”]

[et_pb_column type=”4_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text”]

As a high school student, Ayanna had excelled in an advanced placement program at a reputable private academy. She said high school had come easy to her. College hadn’t started out so trouble-free, however. Ayanna’s chemistry course had become her most pressing concern; she’d “bombed” her first two tests, which was particularly unsettling because this was the area in which she was most interested and was considering majoring. When I met her, Ayanna was thinking about changing her major to an “easier” discipline. She was contemplating pursuing a ministry degree.

Ayanna’s underlying dispositional problem was evident to me from our first academic improvement session. (Recall from Part I that disposition involves our state of mind.) Since high school had been a “breeze,” she’d come to believe that learning was easy. “It just felt like all the pieces fit together,” she recalled about high school. In fact, Ayanna believed that if learning wasn’t easy, then something must be wrong.

Here’s what Ayanna was trying to tell me:

She expected to work harder in college. “Easy” did not mean the absence of hard work to her. (Students often lack the vocabulary to accurately describe their academic experience.) She described the feeling of learning as being “natural.” Ayanna’s religious beliefs also contributed to her faulty disposition. She believed that experiencing troubles might be a sign that she was operating outside of God’s will. Her highly successful, yet struggle-free, pre-college experience and her religious beliefs fostered an implicit disposition about learning, which, when summarized, equated to “If I’m in the right major, then learning will feel less forced and more natural.”

When I considered Ayanna’s history, I empathized with her. I understood her logic. It made sense to me. I also knew that if I didn’t help her shift her attitude about learning, then she wouldn’t make it too far in college.

As author Paul Ramsden affirms in Learning to Teach in Higher Education, to become good teachers, educators should first understand their students’ prior learning experiences. My “diagnosis” was that Ayanna’s pre-college academic experience and her interpretation of a religious belief worked together to cultivate a problematic academic disposition.

My goal wasn’t to change Ayanna’s attitude in one session, though I realized that I may get only one shot. Rather, my aim was to reveal her problem’s source and offer an attractive alternative perspective. I was confident that if I accomplished those objectives in a compelling way, then Ayanna would work out the solution herself.

The following four steps helped Ayanna (as they’ve helped countless others) find her way forward:

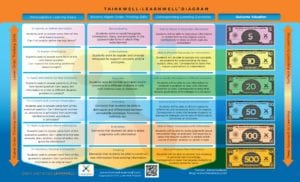

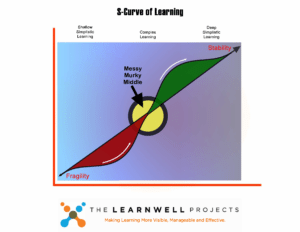

Step 1: Get Visual – Use visual tools

- Dispositions are abstract constructs. I use visual tools to make the process more accessible and pliable. Below are two examples of such tools.

Step 2: Break Up the Silos – Connect non-academic and academic experiences

- Students have been learning since they were born and continue to learn every day. I use their informal learning experiences to demystify academic learning.

Step 3: Ensure Connectivity – Require a metacognitive reflection

- The student and I deconstruct the experience and explicitly apply the metacognitive insights and strategies to specific courses, academic tasks and situations.

Step 4: Feedback and Follow up

- I provide feedback and direction for moving forward. I always ask students to follow up with me as they work through the implementation process and definitely after their first graded task.

Ayanna noticed an immediate difference in how she managed her thoughts and emotions while learning. Her statements indicated that she was shifting from an external to an internal locus of control. She realized that while chemistry won’t change for her, she can change how she processes chemistry. What an empowering position!

Ayanna survived – no, actually thrived – in the chemistry program! The last time I saw her, she was considering options for graduate school to pursue an advanced degree in chemical engineering.

Stay tuned for Part III! We’ll examine some misconceptions that contributed to Ayanna’s faulty disposition. You’ll also learn about the conceptual problem that made Marcus want to strangle his professor.[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column]

[/et_pb_row]

[/et_pb_section]